Software engineers isn’t the first group of professionals that comes to mind when discussing ethics, but their job consistently demands analysis of development, testing, and deployment of applications that support the health, safety, and welfare of the public. Ethics about self-driving automobiles has been a highly controversial topic ever since Daimler-Benz and Ernst Dickmanns demonstrated autonomous driving on a crowded highway which included passing of other cars at speeds up to 81 mph in October 1994. Indeed, the moment an algorithm was expected to choose to swerve or brake in order to avoid collision was the moment human beings began asking, “should it?” Before long, the ethics behind the algorithms driving autonomous automobiles were under fire and so the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) established the requirements for machines that are expected to emulate human skills and the implications of their design in the June 1996 issue of Mechatronics for the Design of Human-Oriented Machines.

The first requirement and expectation outlined by IEEE involved aspects of work psychology. The example provided involved a risk assessment which would be best performed by a human because of the ethical decision that was required. Furthermore, evaluation of the five requirements sets a clear expectation: fully autonomous systems should be reserved for uniform, repeatable situations, with known expected results such as binary, or logical, circumstances. Situations that can be best described in a ‘fuzzy way’ is most suited for systems offering automatic control that is manually limited or authorized. It is desired that the operator remains responsible and able to take control at any time.

Fast forward to May 2012 when Google licensed the first self-driving car in the United States. The car still offered the driver the capability to take control of the vehicle using standard steering and acceleration methods. Through proven reliability, Google deployed the worlds first fully driverless ride on public roads using a vehicle without a steering wheel, floor pedals, test driver, or police escort in September 2015. The passenger was blind and unable to provide human assistance even if it was required. Google’s project Waymo’s principle engineer, Nathaniel Fairfield, claims that the six years of work developing the technology was sufficient to handle even the most challenging situations during the trip, but did they really cover all situations?

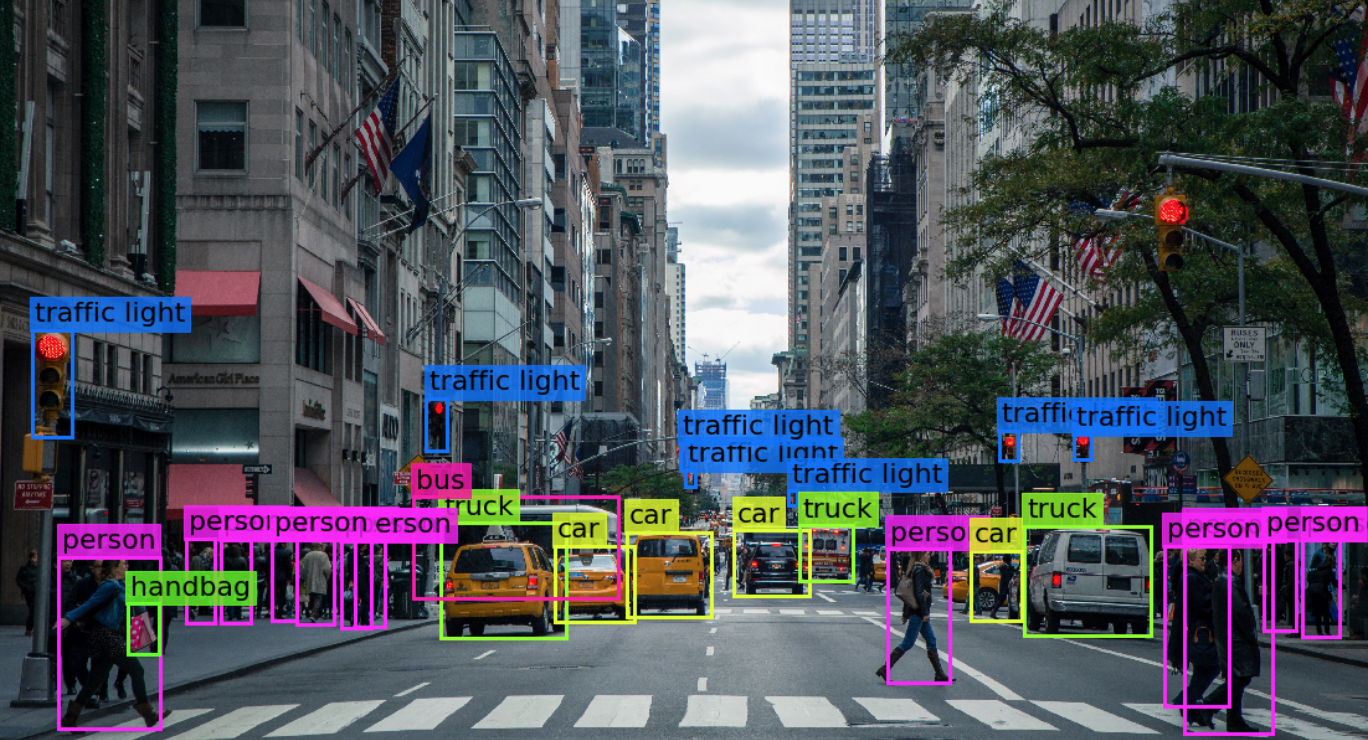

The third principle of the code of ethics for software engineers’ states “engineers shall ensure that their products and related modifications meet the highest professional standards possible.” While, undecidedly, six year of data collection and test drives will provide simulations and results for most situations encountered while driving. Operating a motor vehicle is still an activity that, many software engineers argue, encounters predicaments that are best described in a ‘fuzzy way’. For example, an old woman and her granddaughter are crossing the street in front of a driverless car. Unfortunately, collision is unavoidable but swerving would result in striking just one person. The car is programmed to break immediately to minimize casualties in this situation, but it’s not programmed to decide who lives and dies. This situation would best be handled by the vehicle immediately breaking while providing an alarm and allowing the operator to take control of the vehicle to minimize casualties.

It is unethical to deploy a machine capable of killing without allowing a method for licensed human passengers to take control of the machine in extreme and uncertain circumstances; moreover, this is especially true when a licensed human operator is readily available. Driving a car is an action that has a complementary work allocation between the vehicle and the operator. Sensors supporting self-driving vehicles can dramatically increase response time and minimize hazards during operation, but they should not replace the decision-making process related to high risk situations. Simply put, algorithms do not contain ethical decisions.

[1]G. Schweitzer, Mechatronics for the Design of Human-Oriented Machines. IEEE/ASME, 2020.

[2]”Why Self-Driving Cars Must Be Programmed to Kill”, MIT Technology Review, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.technologyreview.com/2015/10/22/165469/why-self-driving-cars-must-be-programmed-to-kill/. [Accessed: 25- Apr- 2020].